I was listening one evening to a casual exchange between my wife and my elder daughter. It began like any other story, a recollection of days gone by, a fragment from memory stitched together with laughter and warmth. My wife narrated, in striking detail, an incident from my daughter’s childhood: the first visit to a salon, the nervous tears, the attempt to soothe her with ice cream, and the tender patience with which the moment was handled. Yet as I listened, I realised that the scene was not hers to tell. It was mine. It was I who had held my little one close in that salon, I who had watched her resist the unfamiliar scissors, and I who had pacified her with the promise of sweetness. The memory was carved into me, but it had been gently repainted, as if my presence had been replaced by another hand upon the canvas.

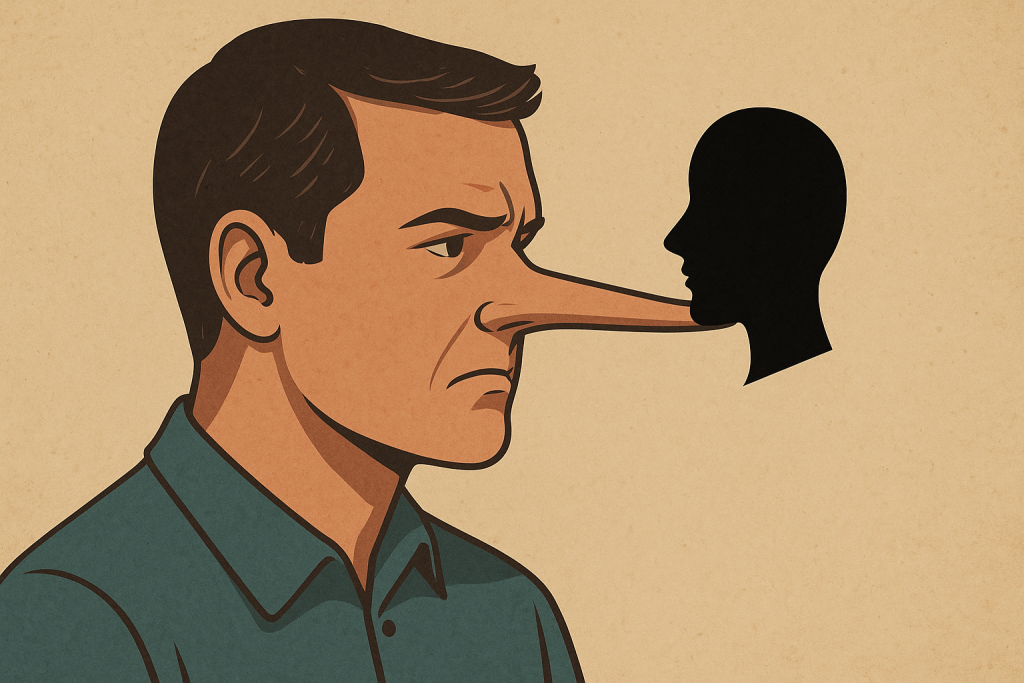

At first, I thought it was a slip, a harmless substitution. But the more I listened, the more I noticed such retellings, the subtle shifting of roles, the small additions, the borrowed details. Not malicious, not intended to harm, yet something in them disturbed me. They were stories transfigured by what many call “white lies.” Later, I discovered the same pattern in a close friend and colleague: a habit of narrating with embellishments, of slipping in fictions, perhaps to make me happy, perhaps to make herself feel significant. It took me years to unravel the pattern. When I did, I found myself not merely confused but wounded. For to realise that someone with whom you share the deepest intimacy has built their fabric of closeness upon threads of untruth is profoundly unsettling.

This personal experience opens a larger question: Why do people lie? And why, even when lies are small and seemingly harmless, do they leave behind a sense of betrayal?

The Roots of Deception

Psychologists have long studied lying, uncovering its layers with scientific patience. At its simplest, lying is the deliberate distortion of truth, an intentional act of saying something one knows to be false. Yet the motivations are complex. Researchers outline several psychological drivers:

-

Self-Protection: The most common lies are born of fear. A child denies breaking a vase, an adult conceals a mistake at work, both are attempts to escape punishment or blame. The instinct to lie here is bound to survival.

-

Self-Enhancement: Another root is the desire to appear greater than one is. People inflate achievements, alter details of their past, or exaggerate stories to earn admiration. In these cases, lies are an instrument of pride.

-

Altruism or “White Lies”: Sometimes lies are spoken with the intention of sparing another’s feelings. A friend says you look well even when you are visibly unwell, or a parent invents a comforting story to soothe a child. These are framed as kindness, yet their ethical standing remains debatable.

-

Habitual Compulsion: For some, lying becomes second nature. Psychologists describe this as pseudologia fantastica, where lying is almost compulsive, blending imagination and reality until even the liar struggles to separate them.

-

Power and Manipulation: Lies can also be tools of control. Politicians, con artists, or abusers use deception to shape the perceptions of others and maintain dominance.

In each of these lies, whether small or large, intentional or casual, there is a psychological gain. One secures protection, admiration, ease, or power. But each lie also costs something profound: trust.

The Fragile Fabric of Trust

Trust is the unseen thread that binds human relationships. It is not built in a single moment but layered through countless exchanges where truth is shared. The moment a lie is uncovered, that thread frays. The wound it inflicts is not only the falsehood itself but the collapse of certainty.

A spouse who lies about something small leaves behind a lingering doubt. If she could alter one story, could she not alter another? A friend who repeatedly hides truth, even for one’s supposed benefit, creates a sense of instability. Do I truly know this person at all? Psychologists note that betrayal trauma often arises not from the scale of the lie but from the identity of the liar. When lies come from strangers, they irritate. When they come from those closest, they devastate.

The pain of lies lies not merely in deception of others but in self-deception. A person who lies frequently begins to weave falsehood into the fabric of their identity. Over time, they live a life that is half-constructed, half-invented. What begins as a strategy to protect or please ultimately erodes authenticity, leaving a hollow sense of self.

The Psychology of the “White Lie”

Defenders of lying often appeal to the concept of the “white lie.” They argue that small untruths can smooth the edges of human interaction. Is it not kinder to praise a poor performance than to wound with blunt honesty? Is it not more compassionate to hide one’s disappointment than to expose another to pain?

Psychology, however, offers a sterner view. Studies reveal that recipients of “white lies,” when they eventually discover the truth, often feel more betrayed than if they had been told the harsh fact at once. Furthermore, habitual white liars often underestimate how easily their deceptions are detected. Even without confrontation, the body knows: tone, expression, and gesture betray insincerity, leaving behind unease.

The question, then, is not whether lies can sometimes soothe, for they can, but whether they ever truly serve. A comfort purchased at the price of reality is fragile comfort.

The Trauma of Discovering Lies

My own confrontation with lies in intimate relationships was not a dramatic revelation but a slow dawning. The trauma was not in the individual falsehoods but in the pattern, in the recognition that the ground beneath me had been less solid than I thought. Many who experience betrayal describe this same sensation, as though the map of one’s life suddenly shifts, familiar territories marked as false.

Psychologically, this creates cognitive dissonance: the painful clash between the image of the person one loves and the reality uncovered. Such dissonance can lead to anxiety, depression, or even a complete rupture of relationship. What is most striking is that the liar may have lied for trivial reasons, without malice. Yet the wound inflicted is grave.

Why We Must Resist Lying

The ancient dictum “सत्यं वद, प्रियम् वद, मा न ब्रूयात् अप्रियम्” — speak the truth, speak what is pleasant, and do not speak what is unpleasant — captures the fine balance between honesty and compassion that Indian philosophy so deeply values. Truth is upheld as the highest virtue, yet the sages remind us that truth must be tempered with sensitivity. One must not hurl truth like a weapon that wounds, nor disguise falsehood in the name of kindness. At times, silence or a gentle rephrasing may be wiser than a blunt declaration that inflicts needless suffering, an approach we might today call diplomacy. Yet this is never a sanction for lying, for falsehood erodes the integrity of the speaker and weakens the sacred fabric of trust. Instead, this teaching calls us to let truth flow with tenderness, so that it preserves its purity while also nurturing harmony in human relationships.

In the end, the psychology of lying shows us less about deception and more about truth: how essential it is for the flourishing of the human spirit. To lie is to betray not only another but oneself. Every falsehood, however small, chips away at integrity, corrodes trust, and leaves the soul fragmented.

There is a haunting passage I once wrote, and it has returned to me with renewed force:

I would pardon a person who kills me by stabbing, but if you are planning to tell me a lie, you better kill me.

This is not exaggeration. A lie is not a deception of another alone, but a betrayal of one’s own self. A wound from a knife scars the body; a wound from a lie scars the very ground on which human connection stands. To lie is to forsake truth, and without truth, there can be no authentic love, no enduring friendship, no society that does not rot from within.